In an earlier May '70 post, I described how, the day after the Kent State massacre, NYU students seized a government-funded computer and demanded the school put up bail for one of the Panther 21, political prisoners eventually exonerated.

The Courant Institute wasn’t the only NYU Downtown turf occupied by rebel forces during the student strike. This piece is about the basement of Kimball Hall, a dormitory there. This was an occupation that I played a small role in and that my old 'rade Lee, with whom I consulted before writing this, was central to.

Why seize a basement? The thing is, Kimball housed NYU's print shop—a sizeable operation for a school with a student body in the five figures, and a huge potential resource for the movement. It might have been grabbed earlier, but was certainly in our hands by May 5. (Shit, I hate having to do this, but a word for the young'uns who spent last semester working at Kinko's: before xeroxing, scanners, photoshop, ink jet printers. laser printers and all, printing was a complicated, arduous, very dirty, sometimes dangerous job, which required a whole mess of steps and many hours between typing your flier and getting a couple thousand of them to hand out.)

Kimball became a political center for the student strike not just at NYU or even the city, but the country as a whole. The credit for that goes to the NYUers who wisely called in a small but respected printing collective called the WIMPs. That stood for Workers In Movement Printing, a name taken the year before when the old SDS regional office in New York and its printing equipment had been seized from the Weathermen. The Weather folks denounced those who booted them in a well-executed midnight raid as “wimps” (but somehow never managed to take the print shop back).

The WIMPs, a core of about 10, brought with them not only artistic, layout and mechanical skills but a valuable political outlook honed by members’ participation in various struggles through the ‘60s. Notable was their non-sectarian approach. They would take on printing jobs for anybody generally within the camp of the forces of sweetness and light. For instance, there was this new-fangled Gay Liberation stuff that sprang up in the wake of the Stonewall Rebellion the previous fall. Many mainline and lefty printshops were less than welcoming when these folks came around. Not the WIMPs, who printed practically every important flier, pamphlet and poster in those heady first months.

So as soon as they moved into what would be their home for many days to come, Kimball Hall, the WIMPs and NYU occupiers did two things. They started printing fliers and posters for the strike, and they started meeting about how the print shop was to be run and how it could be kept secure from administration efforts to get their communication center and hundreds of thousands of dollars worth of equipment back. As opposed to setting up a heavy security system, the collective decided the best security was to open the print shop up widely to anyone who wanted to come in and print stuff for the strike. It worked great.

As opposed to setting up a heavy security system, the collective decided the best security was to open the print shop up widely to anyone who wanted to come in and print stuff for the strike. It worked great.

I remember being there once in the first days when an artist strolled in with some drawings he had done for posters—this was a common occurrence. Somebody present griped a little because one of the designs showed four small coffins hanging off the ends of rifles being aimed by troops in formation: this was too pessimistic, defeatist, something like that. The critic was quickly reminded of the collective’s openness principle.

Folks showed the artist how to blow up his (I recall it was a guy, but can’t swear to it) artwork, and to help make a negative, burn and clean up a plate for the printing press. While it was all in process, including the drying of the posters, he was encouraged to think about how these posters were going to get around and instructed in the fine points of wheatpasting.

The crew I brought down from Taft High School in the Bronx to put out the new issue of their underground paper Rip Off (which in the spirit of The Black Panther used pictures of guns to fill blank spaces and divide articles) were accorded the same respect and help as someone from a university strike committee with a call to a major demonstration.

This approach made the Kimball printshop a major clearing house for strike information and culture. If someone was leaving NYC for, say, Kentucky, they’d stop by and pick up a bunch of fliers or pamphlets and a roll of posters on their way out of town. And some of the folks who came in from the campus or the street stayed and became part of the Kimball crew.

The WIMPs didn’t just print for others, but produced their own art and propaganda. Lee, I believe, was the one who took the famous picture of Mary Anne Vecchio kneeling over the body of Jeffrey Miller and blew it up, all grainy, with the word "AVENGE" in runny letters across it. Thousands of these posters went out of Kimball and were slapped up on walls across New York and around the country.

We used every sheet of paper, every can of ink in the place. One lovely touch was the writing of a carefully-composed letter soliciting donations for bail for the Panther 21. It was printed on NYU stationary, with President James Hester’s signature attached, machine-stuffed in NYU envelopes, run through the on the address-o-graph with the NYU alumni list loaded and stamped in the NYU postage meter. We were told that a couple of thousand bucks actually came in to the Panther defense office!

With the supplies exhausted, and the crew as well, the WIMPs and others who had made sure the place was staffed and running 24/7 for over a week left. NYU had threatened but never made a real bid to evict them by force, a product of the administration decision to get the kids off campus and let the strike wind down on its own—-and of the open and inclusive policy that meant that the whole movement saw Kimball as liberated territory, our territory, and were ready to defend it, if push had come to shove…

Click here to read this series from the beginning.

Four further segments, closing out the events of May '70 and its impact, tracing the struggle to keep the memory alive and drawing few lessons are on the drawing board for 2011. Watch this space...

May 28, 2010

May '70: 19. How To Build A Movement Center

posted by Jimmy Higgins

May 27, 2010

BP's Gulf Blowout And Our Future

posted by Jimmy Higgins

[My friend M sent me the following thoughts which I post with permission.]

Our son-in-law, Lee, earns his living as a fisherman in Key West. Has done so for 30 years. Today is his 52nd birthday and he is now, effectively, jobless for the rest of his life. Being a small fisherman has always been an iffy proposition, because you're dependent so much on the weather, and for the last few years, the weather has become totally unpredictable. Also for the past five years NOAA has been imposing increasingly severe restrictions on what fishers can catch -- how much and when and where -- all in the name of preserving fish populations.

The intent of these restrictions would be believable if the same restrictions were placed on sportsfishers, but until this year, that hasn't happened. Instead, commerical fishers are restricted from catching, say, grouper in certain weeks because they're spawning, and they have to sit idle while sportsfishers pack them in, put them on ice, and take them home to their families and friends.

Why does this happen? Because Tourism is king in Florida. The giant cruise ships come into port regularly in Key West, and dump their loads, polluting the area, with disastrous effects on the coral. And the Navy moved their firing operations to the Keys when protests finally closed Vieques. So things have been hard for Lee and his fellow small fishers lately -- extremely hard since the recession, because tourism is down quite a bit and Lee sold most of his fish to local restaurants and the main fish market in Key West. That market closed two weeks before the oil blowout.

Lee has been scrambling for work -- any kind of work. Captaining boats, scraping barnacles off boat bottoms, anything to bring in money. He's a worker, always has been, and this is very hard for him. He's also become a local spokesman for the small fisher community because he's smart and articulate and a no-bullshitter. Since the oil blowout, he and his fellow small fishers and others in the Keys who are out of work because tourism is down have all taken haz/mat training at the local college, at a cost of $550 a head.

BP gave the college a grant to run the training, a few thousand dollars, and also the promise that those who completed the training would be reimbursed for their costs. Of course they're all hoping for work with BP to help clean up the oil when it hits -- which it will do eventually, and get swept into the Gulf Stream and get carried to other Caribbean countries, but also to the coasts of Europe and Africa. The dispersants, highly toxic to humans and all living creatures, will break up the oil into tiny drops making it less visible on beachers but infinitely harder to deal with. Like sending coal ash into the air.

I am put in mind of the lyrebird, which resides in the Indonesian rain forest. This bird is noted for its amazing capacity to imitate the sounds of the forest all around it, incorporating the sounds into its mating song. In recent years ornithologists have recorded the lyrebird's songs, which include the sounds of the bulldozers and chainsaws cutting down the very trees around it. That's how I see Lee and his fellow fishermen, working to save the ass of the industry that has spelled their doom.

I agree with Bill Fletcher's article -- we just watch and do nothing. We feel hopeless. We all know that nobody at BP will be prosecuted. Oh, probably the CEO will step down, but there will be someone new and nothing will change. Just recently, Biden and Kerry were promoting Big Oil, saying how dependent we are as a nation on BP to provide oil for our war in Afghanistan. This is why the antiwar movement has to be linked to the environmental movement.

We can't really tackle the Fossil Three (oil, gas, coal) and their radioactive playmate Big Nuclear until we confront the fact that this nation's only purpose is as a War Machine. And we can't really stop the War Machine until we deal with our abject and unnecessary dependence on fossil fuels.

We need to start a grassroots movement for solar -- as an individual solution for those who can manage it, and in coops, something akin to the Food Coop. A solar community bank that would fund people going off the grid. I would look to California to see what's happening there. I think another big part of this fight has to be to unite the Food First people, the Greenpeace types, and those fighting to preserve water and waterways. These are really core to our survival and can be readily understood by people because they directly affect their lives.

I've copyedited a few books lately about these issues -- one about grassroots organizing against factory farms; a book that I did earlier this year and was just sent a copy of called The Fate of Earth -- looking at the impact of the Exxon Valdez 20 years later -- which human communities (and other species) recovered and which were destroyed forever. There's a movement out there but it hasn't coalesced and it isn't very visible. But it's who we're going to have to rely on to combat the neofascist Tea Baggers.

I have begun to think that electing Obama was, in fact, a huge setback for the movement. He's every bit as bad as Bush, as regressive on education and war and financialization and civil liberties. He's a corporatist, 100%. There's no question of him unleashing his "inner FDR," as Bob Herbert called for -- he doesn't have an inner FDR. He doesn't even have an inner LBJ. But he's articulate and deceptive, and that has lulled us into doing nothing. I have finally begun to understand how nobody in the USSR rebelled. We feel there's no point whatsoever. We have no leaders. We have no voice.

Labels: anti-war, Barack Obama, BP, Gulf Blowout, Key West, movement building, oil leak, umemployment

May 22, 2010

May '70: 18: ...And In The Studio

posted by Jimmy Higgins

The May 15, 1970 issue of Life Magazine, a weekly noted for its photojournalism, shocked millions with its unsparing photographs of students killed and wounded at Kent State on May 4. One particular copy was to have an impact that has lasted to this day.

Rock musician David Crosby brought that issue of Life to a studio session for the supergroup he was part of. Originally Crosby, Stills and Nash, it had been joined by Stephen Stills’ old bandmate from the Buffalo Springfield, Neil Young.

All four members of Crosby, Stills, Nash and Young were seen as political artists. Graham Nash who had been in the British Invasion band, The Hollies, had released in 1969 a solo cut "Chicago (We Can Change The World)", which starts with a reference to another frame-up trial of Black Panther Party leader Bobby Seale. (Those who have read earlier "May '70" installments may recollect that the call for a national student strike went out on May Day from a Free Bobby rally in New Haven).

It was Neil Young, though, who took the magazine and disappeared for a couple of hours, returning with the 10 lines that are burned into the consciousness of that generation.

Tin soldiers and Nixon coming,

We're finally on our own.

This summer I hear the drumming,

Four dead in Ohio.

Gotta get down to it

Soldiers are cutting us down

Should have been done long ago.

What if you knew her

And found her dead on the ground

How can you run when you know?

Gotta get down to it

Soldiers are cutting us down

Should have been done long ago.

What if you knew her

And found her dead on the ground

How can you run when you know?

Tin soldiers and Nixon coming,

We're finally on our own.

This summer I hear the drumming,

Four dead in Ohio.

Four dead in Ohio.

Four dead in Ohio.

The group recorded the song on May 21, along with a B-side “Find The Cost Of Freedom” written by Stills. (I had always thought that they recorded it on May 15, and several internet sources cite the earlier date, but the notes to Neil’s Greatest Hits from 2004 say May 21 and his archives are legendary, so I’m going with this.)

Even though their record company tried to back them down because they had another single ("Teach Your Children") climbing the charts at the time. CSNY demanded that "Ohio" be released immediately. Dubs were rushed to LA and New York radio stations within days, and another battle began. Many stations refused to play it, especially the mainstream Top 40 stations on the AM band and the new, insurgent, free-form FM stations were the ones to pick it up and run with it.

Singles were out by June, and in July "Ohio" hit the charts. Though it never got higher than #14, it was on for seven weeks, long enough to etch itself into our brains forever--so much so that I've used lines from the song to title three of the earlier posts in this series in the full confidence that most of those reading them will make the connection.

Click here to read this series from the beginning.

Click here to read the next installment.

Labels: CSNY, KKent State shootings, Life Magazine, Neil Young, Ohio lyics

May '70: 17. May 21 In The Streets...

posted by Jimmy Higgins

Though the national student strike was three weeks old on May 21, 1970, it was not yet over. While this is a day late for the 40th anniversary, I am going to highlight the day in two separate posts.

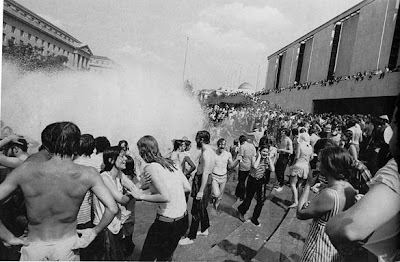

Ohio State University saw one of the biggest clashes of the whole May upsurge with hours of mobile combat as students and townspeople from Columbus took on the Ohio National Guard, even though they were the force that had gunned down four students at Kent State University on May 4.

Actually Governor Rhodes had initially mobilized the Guard at the end of April, because OSU had already blown wide open, even before the Cambodia invasion and the start of the national student strike. As at other campuses, the issue of racism was an initial trigger, with two Black students brought up on charges after a March 13 protest.

On April 20, 100 students in the School of Social Work had walked out, demanding more student voice in decisions, followed a day later by protests targeting recruiters for corporations from the military-industrial complex at a campus jobs fair. Various activist groups united and issued a joint call for a student strike to begin on the April 29, a call quickly endorsed by the student government.

The strike started successfully with picket lines closing classes and a 2000 strong rally on the Oval. By evening it had evolved into a blockade at the campus gates to keep out the Ohio Highway Patrol, called in by the administration. After a night of fighting and 300 busts, student heading for the Oval on the 30th found their campus occupied by the Ohio National Guard. The Guard teargassed a rally of 4000 students that day. Following days saw more fighting and more gas. On the May 4, the administration finally started making concessions, even as the Guard occupation and the strike continued. Once the news from Kent State hit, it was too little, too late. The protests stepped up!

The Guard teargassed a rally of 4000 students that day. Following days saw more fighting and more gas. On the May 4, the administration finally started making concessions, even as the Guard occupation and the strike continued. Once the news from Kent State hit, it was too little, too late. The protests stepped up!

Two days later the administration announced the suspension of classes. OSU was closed effective May 7 at Governor Rhodes’ urging. They tried to reopen it on the May 19. Mistake. Two days later, renewed clashes erupted on the campus and spilled into adjacent Columbus. Scores were arrested. The strike was still on!

Click here to read this series from the beginning.

Click here to read the next installment.

Labels: anti-war, Kent State, May 1970, Ohio National Guard, tear gas

May 20, 2010

May '70: 16. The Other Side Of The Chasm

posted by Jimmy Higgins

40 years ago today, around 100,000 people marched down Broadway in Manhattan. With thousands of safety helmet-wearing members of various construction unions in the lead and American flags everywhere, it was perhaps the largest single demonstration in support of the war during the whole Vietnam era.

As the march traversed the Wall Street area, it was greeted by cheers from crowds on the sidewalks and showered, from the upper floor offices of bankers, stockbrokers and lawyers, with spirals of tape from stock tickers.

Naturally the media gave the march intense play, contrasting it with the campus protests, by that point near the end of the third week of the national strike. And this hooray-for-war rally was in fact a direct outgrowth of the campus explosion. Specifically, it was the culmination of two weeks of orchestrated actions in NYC aimed at pushing the idea that the working class of the US supported the war and hated the protesters, starting with the intensely violent “Hard Hat riot” attacks on peaceful protesters which I wrote about on May 8, forty years after the event.

Two subsequent demos, on May 11 and May 16, targeted the city administration, especially the anti-war mayor John Lindsay (a Republican), with protesters calling him a “commie faggot.”

All were more or less openly organized from the top by Peter J Brennan, the president of the Building and Construction Trades Council of Greater New York and vice president of the city’s Central Labor Council, and it was he who pulled together the May 20th march. As with the May 8 riot, workers continued to be mobilized by their unions and to receive paid time off from the large construction companies to take part.

These demonstrations were localized in NYC and didn’t spread like wildfire, the way the student protests had after the invasion of Cambodia, That’s a phenomenon which requires a little comment, especially for those who weren’t around at the time.

In the first article in this series, I wrote of how deep the split was that the Vietnam War had produced in US society. Those of us who militantly fought to end the war remained a distinct minority, but through our work (building on the heroic struggle of the Vietnamese people to liberate their country), a lot of people had gotten pretty sick of the war.

Still, in a Gallup poll commissioned by Newsweek Magazine very shortly after the killings at Kent State, 58% said that the students were primarily at fault. Only 11% blamed the National Guard. Maybe the numbers were exaggerated, the methodology was flawed, etc, but enough of us came from small cities, from towns, from rural areas--hell, from families--where this was the conventional wisdom to know that Newsweek wasn’t way, way off either.

There was an question of privilege here. The draft was the only way the ruling class could maintain upwards of 500,000 troops at a time in Vietnam and college students had had the best set of options for avoiding or postponing having to show up for the fateful physical. Those who had served in previous wars, and those of our own generation who didn’t have that chance, mainly for reasons of class, had plenty of motive to resent those who did.

Beyond the war, the poll reflected a backlash against the whole new role that young folks were playing in society. We were setting the social norms--in politics, in sexual behavior, in clothing, in music, in every aspect of society, and we were rejecting, wholesale, the values and practices that our elders had lived their lives under and tried to inculcate in us.

In fact, one big reason that the New York City stuff wasn’t a nationwide phenomenon was the legacy of the ‘50s, with its suburbanization, conformity and red-baiting: quite simply, Good Americans (white ones) didn’t demonstrate. Period. It was us, the black sheep, the outcasts, the unAmericans who did.

Click here to read this series from the beginning.

Click here to read the next installment.

Labels: Draft, Kent State, labor, May 1970, Peter Brennan, unions, Vietnam

May 16, 2010

First anniversary of Basire Farrell's murder shows "Hollywood" Booker is on the way out!

posted by Rahim on the Docks

May 15, 2010

May '70: 15. Phillip Gibbs. James Earl Green. Murdered.

posted by Jimmy Higgins

When a unit of the Ohio National Guard wheeled and aimed at Kent State students on May 4, 1970, they fired an estimated 61-67 shots.

Fast forward ten days.

At five minutes after midnight on May 15, local police and state highway cops ordered out by Governor John Bell Williams opened a barrage of at least 460 rounds, mainly from shotguns, at Black students gathered in front of a women’s dorm at Jackson State College in Mississippi.

When it ended more than half a minute later, Phillip Gibbs, a sophomore and father of eighteen-month-old Demetrius, lay dead with two OO buckshot pellets in his head, a third beneath his left eye and a fourth under his left armpit. James Earl Green, an 18-year-old high school student headed home from his grocery store job, had fallen on the other side of the street, behind police lines, the left side of his chest blown away by a shotgun.

Only after the cops had spent 15 minutes or so picking up their shell casings were ambulances called to pick up the dozen or so wounded, and those injured by shattering glass or trampled as people fled the fusillade.

As with the police murders of six young Black men in Augusta, GA days earlier, the media accorded this massacre very different and relatively minimal coverage compared with that given to the students massacred at Kent State. Over the years I’ve heard all sorts of rationalizations for the downplaying of the Jackson State killings.

We knew better then, and we should know better now. The protest at traditionally Black Jackson State was a roiling unorganized thing--as it was at many predominantly white campuses. The three main demands weren’t front and center--and they weren’t at many predominantly white campuses. So what?

The students were riled up by clashes with racist motorists driving by the campus, and a rumor had spread that local Black leader Charles Evers had been shot down. This was not a hard rumor to believe: his brother, civil rights activist Medgar Evers, had been gunned down only seven years before by a Klansman (who was walked by an all-white jury).

And they knew that campuses all over the country were erupting in struggle. So when Jackson State students and local youths started chucking rocks and setting things on fire, they were very much a part of the upsurge that was shaking the country to its foundations that May. All the more so as one of those things was the campus ROTC building!

From that day on, those of us who battled our way through May 1970 have made a point to remind people who speak of Kent State that we must never forget Jackson State. It’s an uphill battle sometimes against historical forgetting, but it is one that won’t cease while veterans of that struggle remain.

And while Kent State administrators spent years trying to bury the massacre there, to their credit, the Jackson State administration, dependent though it was--and is--on overwhelmingly white state education authorities for money, has never repaired the stairwell at Alexander Hall, pocked by 160 bullet and pellet holes. All entering students see the evidence and hear the story of May, 1970, when an organized and heavily armed group of cops, dispatched by the governor, couldn’t intimidate protesting students and finally opened fire on what is now their new home.

Click here to read this series from the beginning.

Click here to read the next installment.

May 14, 2010

May '70: 14. ...'Til It's Over

posted by Jimmy Higgins

Two weeks after Nixon’s 1970 invasion of Cambodia triggered the first and only national student strike this country had ever seen, battles continued to rage on campuses the length and breadth of the country.

Take the University of Maryland at College Park. Striking students and faculty had pretty much shut the place down during the early days of May. In fact, as the fourth installment of this series pointed out, thousands of them also invaded and shut down US Route 1, then the main artery between Baltimore and Washington. Day after day, students poured onto Route 1, blocking it and the state cops mobilized to clear it. Day after day, the pigs attacked the campus, arresting scores, teargassing dorms and frats to the point where they were uninhabitable. and administering savage beatdowns as the students fled. This repression on top of rage at the Kent State murders swelled the ranks of protesters and keep the struggle hot.

Day after day, students poured onto Route 1, blocking it and the state cops mobilized to clear it. Day after day, the pigs attacked the campus, arresting scores, teargassing dorms and frats to the point where they were uninhabitable. and administering savage beatdowns as the students fled. This repression on top of rage at the Kent State murders swelled the ranks of protesters and keep the struggle hot.

The university was shut down by the strike but the administration hadn’t opted for the cancel-finals-and-pass-everybody trick being used at other schools, so the clashes continued. They peaked on May 14, 40 years ago tonight.

One grad who returned to campus to build the strike recalls:There was a lot of teargas the night of May 14. I didn't quite understand the campus politics, but a faculty vote had gone badly and several thousand students headed for Route One in protest.

That night, amid extensive trashing and the U of M Administration building very nearly went up in flames. The country’s campuses were still on fire with struggle!

Governor Mandel had mobilized the National Guard who moved on to campus after students were driven off of Route One. It was ironic, because we all knew that the reason many people joined the Guard was because they didn't want to fight in the unpopular Viet Nam War. I was sorry to see them. They were probably even sorrier being there.

The exchanges of teargas bombs and rocks were the fiercest I had ever seen. People were determined to hold on to their piece of liberated Maryland even in the face of a military occupation. National Guard Commander Warfield's helicopter flew overhead and added a further surreal menace to the whole scene.

We grouped on the hill in front of the Chapel. It was dark and hard to see how many people were holding out, but it seemed like thousands. The crowd ebbed and flowed depending on how many teargas bombs were fired by the National Guard and police from the base of the hill near Route 1.

Click here to read this series from the beginning.

Click here to read the next installment.

May 13, 2010

May '70: 13. The Senate Steps Up

posted by Jimmy Higgins

Forty years ago today, Senators Frank Church (D, Idaho) and John Sherman Cooper (R, Kentucky) put before the United States Senate an amendment to the Foreign Military Sales Act of 1970 which, if passed, would ban the use of any US funds for combat in or bombing of Cambodia. Debate continued until the amended bill passed on June 30, the date on which Nixon had promised to end the invasion of Cambodia.

The Cooper-Church Amendment was a clear sign that dissatisfaction with the prolonged and catastrophic war in Southeast Asia was finally moving Congress to act. But the more immediate impetus for the bill was the great turmoil which had erupted on the country's campuses, and the panic it had awakened in the hearts of America’s rulers.

The back story is fascinating. Joseph Califano, who had been President Lyndon B. Johnson’s principal aide on domestic matters, was now ensconced in Washington as rainmaker and lobbyist for a prominent law firm and a powerhouse in the inner circle of the Democratic Party.

On May 6, he was braced by Yale prexy Kingman Brewster (him again!) to find some way to involve college students in lobbying against the war, lest college kids “destroy some of our major universities if offered no constructive alternative.” Brewster kicked Califano two of Yale Law’s top students to jumpstart a project.

Califano grabbed another veteran Democratic party figure, John Gardner, who was in the process of launching Common Cause, and with Brewster’s proteges came up with the idea of “Project Purse Strings,” an lobbying effort to cut congressional funding for the war in Southeast Asia. Califano and Gardner knew damn well that that was not going to happen any time soon but shined Brewster’s law students on, while deciding to limit the goal to the elimination of spending on Cambodia.

Califano was a busy little fellow that week. He also set up a money conduit to fund the operation. He bagged, in one day, 15 grand each from the heads of Coca-Cola, Hoffman-La Roche, Polaroid, Neiman Marcus and a bunch of other big corporations. Some opposed the war, others did not, but all shared Califano’s concern thatthere was a real danger of losing the best of a generation. We feared that they might turn into a rabid, persistently negative force in our society

and thatit was important to build a student movement pledged to work within the system.

Or, to put it another way, the national student strike had scared the living piss out of them.

Califano and Gardner meanwhile lined up Church and Cooper, respected Senate elders, to put their names on an amendment which was rushed to the Senate on May 13. It called for an end to funding of US ground troops and advisors in Cambodia past June 30, for banning air operations in Cambodian airspace that were not expressly approved by Congress and for an end to US support to South Vietnamese military operations outside its borders.

Weeks of debate and filibuster followed, replete with plenty of lobbying by clean cut, promising (and well-funded) college students. On June 30, the last day of the invasion of Cambodia, the United States Senate voted the Cooper Church Amendment up 58 to 37, making it part of the bill.

This was the first time in US history that a house of Congress had ever voted to cut funding for a war a president was carrying out. It signaled what was to come--Congress finally cut off all funds for the war in 1973, three long, grueling years later, and then it was only a matter of time until those helicopters were taking off from the roof of the US embassy as Saigon was liberated.

I never heard of “Project Purse Strings” back in the day, and I doubt that even many of the participants remember it today. To us, the lesson was obvious, and it wasn’t about what a good idea lobbying was. To force the government to back off from an unjust and unjustifiable war, you had to build a mass movement too large and too militant to ignore, to the point of threatening social collapse. Then they’d listen to us.

Me, I still think that summation shows the correct relationship between electoral politics and government on the one hand and mass movements on the other. Only independent mass movements can keep even the best of elected officials honest, and pressure or frighten them into doing the right thing. All the lobbying and electoral work that had taken place as part of the struggle to end the Vietnam war since the mid-’60s may have helped lay the foundation but those accomplishments paled before what the first two weeks of the May, 1970 campus uprising had done.

Click here to read this series from the beginning.

Click here to read the next installment.

May 11, 2010

May '70: 12. The Forgotten Dead [UPDATED]

posted by Jimmy Higgins

There were six of them, gunned down by the armed force of the state.

I could be talking about the four students murdered at Kent State just seven days before plus the two who would would die later in the week at Jackson State.

But I’m not. I’m talking about six young Black men killed in Augusta, Georgia, 40 years ago tonight. Each was shot in the back by police shotguns, and their deaths were woven into the fabric of struggle and repression that was growing day by day in May, 1970.

Like many an urban rebellion in the ‘60s, it started with the cops. On May 9, Charles Oatman died in the Augusta city jail. He was 16 and mentally disabled. The police announced that he had died in a fall from his bunk. At the funeral home, his body was discovered to have fresh cigarette burns and bruises all over it. Open wounds from a whipping marred the corpse’s back. His skull was caved in. Changing their tune, the cops moved to charge his cellmates with murder.

On May 11, community activists who had been dealing with police brutality issues for a long time met with officials and left the meeting to find 500 furious community residents outside demanding action. A march was called on the spot and soon erupted into rock throwing and looting which went on into the evening.

The governor of Georgia, a foam-flecked racist named Lester Maddox, swung into action. He ordered out the state police to deal with the citizens he called “communists” and Black Panthers. He gave the cops orders to shoot to kill and even to raze “any building they’re in to its very foundation if necessary to get them out.” Maddox followed up by mobilizing 1,200 troops of the Georgia National Guard, who reached Augusta about 1:00 in the morning on the 12th.

By dawn on the 12th, the “Augusta riot” was over and over 80 people were wounded. Six young Black men were dead. None had been armed. All were hit in the back by shotgun blasts consistent with police riot guns.

Why do these ugly police murders belong in a series of articles about the campus uprising of 1970? To us, at the time, it was obvious. These kids were murdered just like the kids at Kent State. Augusta was, in fact, one of the last of the great urban rebellions against racism that shook the US to its foundations in the ‘60s. Those rebellions had helped form our understanding that of the oppression of African Americans was far broader and deeper than a question of Jim Crow segregation in the south. Around the country, leaflets and posters about the Augusta murders started to appear within hours.

Sure, the riot wasn’t on campus, but the folks in Augusta’s segregated inner city knew that colleges around the country were erupting in protests and had in one case been met with bullets. And how was the Guard able to mobilize so quickly, if they were not already on alert to deal with campus unrest?

But even our steps in solidarity with the Augusta rebellion wound up butting up against the ugly realities of life in a society built on, and shot through with, white supremacy and white privilege. If you went through the month of May in 1970, you will always have a visceral response to the names of Sandy Scheuer, Bill Schroeder, Alison Krause and Jeffrey Miller. You may even recall that Philip Gibbs and James Earl Green were the two slaughtered at Jackson State. I hope this piece has jogged your memory about Augusta.

UPDATE:

When this was first written in 2010, I reported that I had been unable to find the names of the six whose lives were snatched from them by the Augusta cops forty years before. Then filmmaker Banks Pappas, who made an independent documentary on the Augusta uprising (see his trailer here) contacted me after reading the original version. Thanks to him, I offer for your respect and your remembrance:

Mack Wilson, Jr.They deserve to be recalled with the others as young people whose lives were taken in May '70, at one of the historic peaks of the long struggle to bring into being a better world...

John (Johnnie) Stokes

William Wright, Jr.

Charlie Mack Murphy

Sammie Larry McCullough

John Bennings

Click here to read this series from the beginning.

Click here to read the next installment. Read more!

May 10, 2010

May '70: 11. The Campuses Start To Empty Out

posted by Jimmy Higgins

Before following up on the strategy that college and university administrators were adopting to defuse the strike on many campuses, I want to tip the hat to the Canadian radicals who took a page from Richard Nixon and invaded the border town of Blaine, Washington from Vancouver on May 9.

Declaring they were doing it to strike at "sanctuaries for aggression," the 500 or so young militants vowed that they’d go no further than 19 miles into US territory, the limit Nixon had placed on his Cambodia invasion. That far they didn’t get, retreating in good order into British Columbia after trashing the Bank of Commerce and most of the vehicles on a freight train hauling new autos. A joke, certainly, but a pretty pointed one and the first foreign invasion of any of the United States since the War of 1812.

Yesterday I wrote of how University administrators around the country were adopting or contemplating a strategy of proclaiming agreement with their protesting students and shutting down the campuses., declaring the school year ended early. This, folks who have read the third installment of this retrospective study may recall, was the strategy adopted by Yale president Kingman Brewster as he faced the May Day protests in New Haven.

[An interesting sidenote: Brewster had adopted this strategy after holding a secret meeting held in rural Massachusetts under the guise of a picnic. The other party there was Archibald Cox, head of the Harvard Law School, who shared the mistakes made at his campus the previous year when the administration sent in the cops in to retake an occupied building. Their brutality enraged many uninvolved students and triggered a hard fought, weeklong student strike.]

A couple bloggers at the left liberal Daily Kos site who had been at Michigan State in May '70 wrote comments about the piece I reposted there yesterday. A woman named Pam described how intense the struggle had been: During this period I was a student manager at the MSU Union Bldg. The riots that broke out because of the Cambodia invasion occurred when I was on duty at the Union. It was real bad.

After days of intensifying struggle, suddenly things changed according to a DKos regular who goes by austinblue:

We were directly assaulted with tear gas fired into the building air intakes. I had received assurances from the state police that they would not do that because I had several groups of elderly citizens meeting there. Several students who had been on the street came in to clean the gas out of their eyes and I recruited them to help me take care of our elderly visitors.As I recall, Michigan State was roiling. Then President Wharton cancelled classes just before Mother's Day weekend, and poof, the air just went out of the Movement.

Naturally, most students seized the opportunity, when it presented itself, to get away from campus and start chasing summer jobs early. But not all did. My bud, Mindy who was at NYU Uptown with me recalls:

I was astonished at how effective the tactic was. Up to that point I thought he wasn't paying attention (remember Nixon watching football a couple years later?), but it turned out that he outplayed us, or maybe he just lucked out. Whichever, the strike lost all momentum after the campus emptied out for a few days, and I always saw that last day of classes before the weekend as the peak of the Movement on our campus.At my campus, as at hundreds, maybe thousands across the country, students shut the school down. I don’t remember now how it happened but I know that there were no final exams and there are no grades on my college transcript for the second semester of 1970. It’s just 16 credits of PASS.

The school’s administration was amazingly cooperative, as Mindy indicates. If folks were using the university’s resources to provide sanctuary and real education to local high school kids or Serve the People programs to the community, they didn’t mind. Those who stayed in those free dorms and worked themselves to the bone all summer to create a different kind of institution with a different kind of relationship to the community were welcome to do so. Professors who wanted to help were encouraged to do so.

Somehow contact was made with students at the nearby high schools in the Bronx, the girls at Walton and the kids at Taft, and at Lehman College. Within a few days there was a massive march down the Grand Concourse. It wasn’t just students; lots of regular people from neighborhoods in the Bronx came out to protest. Speakouts were held on campus over the next few weeks. Workshops were developed on the war in Vietnam, the expansion into Cambodia, U.S. imperialism, racism, feminism. We set up a summer day care center for Bronx parents who lived near the school. We demanded, and got, free dorm space for the summer.

I don’t know how we did it. I don’t remember what it was like day-to-day. But I do remember that I was no longer a quiet college student, working hard in my classes and at my off campus part-time job while also trying to get a better understanding of how my country worked. I had become, and after many twists and turns, remain, a committed political activist.

I’d like to think that the folks who ran NYU were open to developing a new vision of their institution, but we didn't believe it at the time, and nothing that they have done since has ever suggested we were wrong. They did it largely because while we were only a handful, the respect we had won from many who would be returning in the fall made them think twice about trashing us. And the ties folks like Mindy were patiently starting to build in the West Bronx were turning our attention away from our student peers and campus affairs and toward the community. And they looked good doing it. All in all, it was a bargain for them.

Click here to read this series from the beginning.

Click here to read the next installment.

Gotta Make Way For The Young Folks…

posted by Rahim on the Docks

May 9, 2010

May' 70: 10. The Peace Crawl & The Handwriting On The Wall

posted by Jimmy Higgins

Forty years ago today, 100,000 angry people descended on Washington for a mass march to end the war.

Preceding years had seen larger marches, to be sure, pushing toward a million strong on occasion, like April 1967 in NYC. But this one had been called only a week before, in response to the Cambodia invasion. Normally these exercises took months and months to pull together—getting the permits, choosing the slogans, printing the literature, spreading the word, renting the buses, mobilizing local groups to take part. And let’s not forget fighting over who should speak on the program.

I didn’t go to DC that Saturday. The NYU Uptown SDS chapter didn’t go, Nobody I was in touch with from the Washington Square Campus did either, if I recall correctly. Relatively few of the revolutionaries and other activists at the core of the campus upsurge on the East Coast did.

Partly, we had simply tired of Peace Crawls, as we had uncharitably taken to calling them. Starting in 1965, there had been two Big Marches a year, one in the spring and one in the fall, usually in either DC or NYC (and simultaneously in the Bay Area or L.A. or both). Sometimes, as with the March on the Pentagon, they marked a big step forward for the movement, usually because they took some unexpected action. More often they demonstrated that an awful lot of people wanted the war over with, most ricky–tick, and served as a reminder that it didn’t seem to be happening.

More particularly, we felt that it was a diversion right then. The unprecedented upsurge which we were in the midst of had been built on hundreds of campuses around the country and that was where the fight was going on. It would be pointless and potentially harmful to pullpeople away from those battlegrounds for a time-consuming roundtrip to a big city many hours or even days away.

In this case, there were countless discussions and debates in small groups, informal collectives, mass strike committees over what to do. Again, to belabor a point made earlier, there was no organized and recognized center to the movement. Had there been one, it might have put out a call that would have meant half a million plus in DC--or 25,000.

The powers that be were, it turns out, plenty scared of that Washington march. This was the stretch in which elements of the 82nd Airborne were moved into the basement of the executive office building and other potential occupation targets. I would still argue that throwing a scare into the bastards wasn’t enough to justify pulling forces away from the campus base areas that had been established. (After all, we had already frightened the shit out of them in November, 1969, when a 10,000 strong militant breakaway from the Big March had laid siege to the Justice Department, causing the Attorney General’s wife --Martha Mitchell, for those with long memories--who had been peering down from the top floor, to exclaim, “It looked like the Russian Revolution!”)

Meanwhile, the strike was about to win—or start folding up, depending on how you looked at it.

By that weekend, the outlines of the enemy’s overall strategy to deal with the flood of protest on the campuses was taking shape. University administrations around the country, a few at first, but with many more watching from the wings, started taking a stance of solidarity with the protesting students and faculty!

More specifically what they did was issue a proclamation with some variation of this message:

You splendid young people are correct. This crisis is no time for business as usual. We are therefore canceling all classes for the duration of the Spring semester. We urgently hope you will pursue the kind of change this country so obviously needs by, oh, for instance, going back to your hometowns to build opposition to the war and support for social justice.

Oh, yeah, no finals. Everybody gets a pass for all course work.

And the dorms are closing.

Mao Zedong’s famous dictum is that the guerrilla is like a fish swimming in the sea of the people. Well, for the activists, the campuses were our sea, and they were being drained a month ahead of schedule.

We had pulled it off. A national student strike, the dream of campus activists since the early ‘60s, was shutting down the bulk of the American higher education system.

So what?

Now what?

Well, we still had the wind at our backs, and the coming weeks would see further gains won, but those two questions would loom larger as we kept building the struggle.

Click here to read this series from the beginning.

Click here http://firemtn.blogspot.com/2011/05/may-70-8-forgotten-dead-of-augusta.htmlto read the next installment. Read more!

May '70: 9. Violent Backlash

posted by Jimmy Higgins

I was there when the reactionary "white terror" kicked in.

After the Kent State shootings, a New York City-wide demonstration had called for Wall Street on Friday—that was 40 years ago today, on Friday, May 8, 1970. I have no idea who called the demo, though it targeted the financial center of US capital and was around the three demands: US Out Of Southeast Asia, End Campus Complicity With The War Machine, and Free Bobby Seale And All Political Prisoners.

A small crew of us from NYU Uptown were there—I can’t swear to it, but I think it might have been Lon E. Bich and maybe Jim Bean. I remember the big banner for Bobby, and I remember how many high school kids seemed to be in the crowd of a couple thousand, crammed into the narrow streets of downtown Manhattan.

Suddenly, just before noon, as Wall Street types on lunch further crowded the area, there was a big stir about 20 feet from us. A tight column of dozens of guys wearing construction helmets with a couple American flags was wading through the crowd. Almost immediately it became clear that they were not just pushing protesters out of the way, but slugging them, beating them to the ground and kicking them. (Some Wall Streeters helped the injured. More joined the attacks.) We tried to rally the other kids around us to counterattack, but were physically held back by a bunch of Gandhian types, babbling about how we shouldn’t meet violence with violence. We didn’t want to have to fight our own people to get to the thugs, who were cutting through the crowd pretty quickly, so we faded with the other protesters, who were dispersing damn fast.

We tried to rally the other kids around us to counterattack, but were physically held back by a bunch of Gandhian types, babbling about how we shouldn’t meet violence with violence. We didn’t want to have to fight our own people to get to the thugs, who were cutting through the crowd pretty quickly, so we faded with the other protesters, who were dispersing damn fast.

These were construction workers, we figured out, from lower Manhattan projects like the World Trade Center. Their attack was clearly planned. The little column we saw was one of four to hit the demo simultaneously from all sides. They moved on to attack City Hall, where the flag had been lowered to half-mast for the Kent students on the orders of Mayor Lindsay. Some spotted an anti-war banner at nearby Pace College (never a hotbed of struggle), and a crew peeled off to tear it down—and to savage a couple of dozen clueless Pace students, male and female, on the street and inside the building. They were taken to join scores of injured demonstrators being treated at area hospitals.

First I want to dispose of the myth that this was spontaneous, or a peaceful counter-protest that "got out of hand." The construction workers were kept on the clock for the day of the attack by the firms they were working for, and they were organized and led by officials and goon squad members from the Building Trades unions (and, as we learned later, from some needle trade locals as well). Not only did they wear helmets, but many carried lengths of rebar or chain, or tools.

The cops stood by passively and did jackshit to stop the attacks at any point. I’ve never been convinced one way or the other about why this happened, whether it was because they sympathized individually or because the police bureaucracy, without consulting the elected leaders of the city, decided to not to step in. 240 Centre Street certainly should have known it was coming--they’d been warned early that morning in a phone call from a construction worker whose foreman had tried to recruit him to take part.

Whether or not it was coordinated from the White House, it certainly fit right in with the main line of the Nixon Administration’s attack on opponents of the war: we were a vocal and countercultural minority or, as Nixon has described us the day after he made his Cambodia speech, "these bums, you know, blowing up the campuses." There was in America, Nixon had proclaimed the previous November, a Silent Majority, who supported the war, the American way and, by implication, his administration.

Now here were actual workers, brawny men, many of them WW2 or Korea veterans, shortened into "Hard Hats" in big bold-type newspaper headlines, stepping up to bloody the bums and uphold the Vietnam War. There is no question that subsequent larger and less violent Hard Hat demonstrations were coordinated with the administration.

On Monday May 11, a couple thousand were mobilized and paid by the same contractor/building trade union forces and joined by longshore locals and other war supporters in rallying to denounce Republican mayor John Lindsay as “a commie bastard.” Another was held on May 15, intended to counter the continuing drumbeat of anti-war protest.

No matter how coordinated this may have been from above, we were under no misapprehensions about what it represented. A large chunk of the white section of the working class in the US was offended and threatened by the anti-war movement and more generally by the long-haired, sex-drugs-and-rock&roll youthquake that it grew out of. There were plenty who would attack us, and many, many more who would applaud anyone who did. And while we might be on the rise historically, and on the offensive at the moment, we were still a minority in the country.

A big question on our plates for the rest of the month of May was how this card would be played. Would Hard Hat Riots spread well beyond their New York birthplace? Would local governments embrace them? Would the construction unions, or some different organizational form, become semi-official stormtroops for the administration?

Click here to read this series from the beginning.

Click here to read the next installment.

May 6, 2010

May '70: 8. Memory Loss

posted by Jimmy Higgins

The sign was hung out of an NYU dorm window. It read, simply

I want to use that sign as a starting point in talking about some largely unsuccessful emotional archaeology I’ve been doing, trying to reconstruct what it felt like to be 20 years old and a revolutionary in the midst of the first national student strike the country had ever seen.

I know I wasn’t expecting to be killed, even though--forty days ago today—the Kent State murders were only two days in the past and in the forefront of everyone’s thoughts.

And that wasn’t what the dorm room sign was about. Those kids didn’t expect to be killed either. They were celebrating the fact that the scope of our movement, the hundreds of new campuses—including high schools—which had gone out on strike since May 4 had pretty much removed violent repression as an option for the ruling class. I quoted John Kaye on the intensity of those days in yesterday's installment. I’ve recently spoken with Mirk and Mindy, who, like me, came out of NYU and we all agree that there is a lot, a surprising amount, from these intense weeks that we just don’t remember.

I put this down to three things.

First we were drinking deep of an emotional cocktail that combined rage, exhilaration and simple exhaustion.

Second, we were in an environment where all of daily life was changed. Classes, papers, tests no longer had claims on students’ time; though they might still worry about such things, as 12+ years of US schooling had trained them to, we were on strike! The struggle demanded that we do new things and do old things in new ways and do them all at once.

In the two or three days following May 4th, I am fairly certain that I spent many hours with kids from nearby Taft High School with whom NYU Uptown SDS had been working, helped them organize a walkout and lay out the second edition of Rip Off, their underground paper, and get it printed by the Kimball collective. The Uptown crew also met to develop programs we were demanding that the administration put in place to serve the West Bronx community. I also seem to recall spending much of my time downtown, centered around stints, including some quickly grabbed zzzs in the middle of the night, guarding the seized Courant computer. And meetings to coordinate activities on the Uptown and Washington Square campuses. Then there was the peace march on Wall Street that the hardhats attacked. And a bunch of us went to City College to support the students there. And…

Third, was the simple fact that we had entered uncharted terrain. The enemy was in retreat, though still deadly. We were, in chaotic fashion, advancing. What should we be demanding—of our school, of the government, of society?

For instance, to return to my touchstone. our SDS chapter had a standing demand that NYU enact an open admissions program for community residents who graduated high school. It was a damn good program, written by some guy named Mike a year or so earlier (we lost track of him when he transferred out), but it had never been anything we had the power to make the administration deal with.

Now things were different, even if the majority of students who were on strike weren’t ready to go as far as open admissions-—concerned what it might do to the value of their diplomas and to tuition rates. Should we do more education to win our classmates over? Set up our own free tutoring programs for grads from Taft and other local high schools to prove to the administration it could work? Force the NYU administration to develop partnership programs with the city officials running those high schools and start taking the first steps?

Lacking experience, absent central coordination, without tested leadership to help us sort through the options, we tried everything, usually without a clear plan and goals.

I’m not sure how different things could have been, given the historical circumstances, but I guess the reason I am writing this multi-part reflection is to identify and salvage some of the lessons of May. ’70, so when history puts something like it on our plate again, we can avoid some of the old mistakes, and make some new ones as we move forward.

Click here to read this series from the beginning.

Click here to read the next installment. Read more!

Labels: Kent State, May 1970, NYU Uptown campus, open admissions

May 5, 2010

May '70: 7. How Can You Run When You Know?

posted by Jimmy Higgins

May 5th, 1970. As Tuesday dawned, the whole country, the whole world, knew about the Kent State massacre. The famous photo of Mary Ann Vecchio on one knee, keening over the body of Jeffrey Miller, snapped by a Kent undergrad seconds after the National Guard ceased firing on Monday, went on the Associated Press newswire that afternoon and was seared into the nation’s consciousness the next morning.

Chip Young, one of several friends who volunteered memories when I started this project, recalls:

I would have been 11. I remember my older brother informing my mom about the killings. Her response: "Oh no, not in America." Perfect moment of shattered idealism.Nan Faessler blipped me a single sentence:

Because of the killings at Kent State, I made a decision to drop out of graduate school and devote my time to working with the anti-war movement full time.John Kaye’s response:

I never went to college, but at the time was living near Marquette U in Milwaukee, working in a Movement bookstore. What the right wing at the time used to call an "outside agitator." Even before the invasion of Cambodia, at that point in my life activism was everything.In these three brief recollections, we see events as they actually unfolded--shock, individual commitment to resist, escalation of the struggle.

When the news hit, especially about Kent State, and shortly after, about Jackson State, things sort of...exploded. I didn't sleep for 3 days, up all night at meetings, silk-screening clenched fists on t-shirts, etc. Demonstrations and whatever else we could think of all day and evening. The only time in my life I ever gave an impromptu speech, to a smallish group of students gathered just south of the campus, about the Panthers, I think.

In retrospect, because what happened happened, it seems inevitable. But things could conceivably have gone another way. Some students fled the campuses and more were pulled out by terrified parents. Ohio wasn’t the only state where the National Guard had been called up--before the end of May, something like 16 governors had mobilized a total of over 35,000 troops. Police forces coast to coast were on high alert.

In a comment when I reposted yesterday’s May ‘70 article at the left-liberal Daily Kos website, a blogger who goes by Empower Ink wrote:

For me, and many other college students, Kent State had a chilling effect in our participation in protests, following so closely to King's and Bobby's assassinations and Chicago '68.While Empower Ink continued her activism, many didn’t or never started because of Kent State. The Beach Boys, a group whose greatness I normally defend to the bitter end, echoed this approach in 1971's disgraceful "Student Demonstration Time" (lyrics by Mike Love, natch) which proclaimed:

While I remained very actively politically after Kent State, through Nixon's impeachment and Raygun's administration, I did not go to a massive anti-war protest until the day after the 1st Gulf War started.

I know we're all fed up with useless wars and racial strifeWe had just seen the iron fist behind the mask of American democracy and we had learned that it didn’t smite only Black people in ghettos and the differently pigmented inhabitants of small countries half a world away. Challenge the system hard enough, and even college campuses could become free-fire zones. If it had happened at half a dozen other campuses, might the movement have been stopped in its tracks?

But next time there's a riot, well, you'd best stay out of sight.

Maybe not, because millions of us were not intimidated but outraged--and driven to act.

In the event, what did happen was that we escalated--and the other side blinked! California Governor Ronald Reagan, who had only a month earlier blustered about having “a bloodbath” on campuses, ordered all of the schools in California’s vast higher education system closed until May 11. College administrators around the country suspended classes, convened campus meetings, issued public statements condemning the invasion of Cambodia and the shootings at Kent State.

Meanwhile, strikes and protests broke out from Portland East to Portland West--and Alaska and Hawai’i too. At least 100 more schools went on strike on the 5th, with hundreds and hundreds more to follow in the coming days. And enraged protesters took the struggle off the campus, like the thousands at the University of Washington who surged onto Interstate 5 and took it over, marching into Seattle.

At NYU, where I was based, the already shutdown campus saw a dramatic escalation when a couple of hundred of us burst into Warren Weaver hall on the Washington Square campus and occupied it. The whole second floor of this unattractive and (it turned out) uncomfortable building was the Courant Institute, which housed a heavily refrigerated, multi-million dollar, state of the art CDC 6600 computer. This monster (whose functions could be performed today by a decent pocket calculator) was funded by the Atomic Energy Commission and crunched numbers to build up the US nuclear arsenal.

The next day, the NYU administration got a telegram reading, in full:

We, as members of the N.Y.U. community occupying the Courant Institute, are holding as ransom the Atomic Energy Commission's CDC 6600 computer. At a general meeting in Loeb Student Center, the people put forth the following demands: the University must pay 100 Thousand Dollars to the Black Panther Defense Committee for bail for one Panther presently held as political prisoner in New York City. Failure to meet this demand by 11 a.m. Thursday, May 7, will force the people to take appropriate action. In addition, if the University Administration should call in police or other authorities, the above action will be taken immediately. In the meantime, no private property will be destroyed.No, we were definitely not blinking.

(Signed) N.Y.U. Community on Strike

Click here to read this series from the beginning.

Click here to read the next installment. Read more!

May 4, 2010

May '70: 6. Four Dead In Ohio

posted by Jimmy Higgins

click to enlarge

May 4 fell on a Monday in 1970.

At some point during the morning, four students each woke up, grabbed a toothbrush, maybe showered, got dressed, probably had a bite of breakfast, and headed out.

It wasn't the proverbial day like any other day. For one thing, over the weekend National Guard troops had occupied their school, Kent State University.

Bill Schroeder and Sandy Scheuer both made their way to their first classes anyhow. Alison Krause figured she'd hit the big anti-war rally scheduled for the Commons at noon. So did Jeffrey Miller, despite the spreading reports that Kent State administrators planned to ban it.

At 12:24, they were flung into history.

Click here to read this series from the beginning.

Click here to read the next installment. Read more!

May 3, 2010

May '70: 5. The Gathering Storm

posted by Jimmy Higgins

May the Third, 1970 was a Sunday.

The main thing about it was that we still really didn't quite have a handle on what was happening. Not did we know what was about to happen. Those who had spent years fighting campus battles--or who felt ourselves part of the broader multifaceted forces of social justice generally known as The Movement--were pretty much as full of excitement and uncertainty as the high school sophomore who had suddenly decided that she would cut school on Monday and head on over to see what was happening at the local college.

With the benefit of hindsight, of course, we now know that forces were gathering which would only one day in the future recast everything that had happened so far and intensify it by an order of magnitude.

What were we doing on May 3?

Though Students for a Democratic Society was gone, and with it any chance of real national leadership and coordination, it would be wrong to overestimate our isolation. Local successor groups and semi-formal regional networks were solidly in place in many parts of the country.

The first thing we did was share information. That was harder in the pre-Internet days, but every nugget plucked from a high school classmate or sib who had gone to a different school halfwayacross the country, every report from the radio, the teevee or the newspaper, circulated immediately.

And we networked. 20 campuses in the mid-Atlantic area had representatives at an emergency meeting at the University of Pennsylvania to coordinate strike activity.

And we organized. In the Boston area alone, organizers at M. I. T., Harvard. Tufts and Boston University were building for mass meetings on Monday to vote on strike proposals, while students at Brandeis met in their dormitories on the 3rd to decide what action to take. More than a dozen campus newspapers around the country endorsed the demands coming out from New Haven rally two days before.

[Interestingly the article from the Harvard Crimson issue of May 4th where I found some of this info reported 1. that a "National Strike Committee" had come out of the May Day rally in New Haven and 2. that there was a fourth demand, Impeach Nixon. A good call, history would prove, but I don't remember it myself, and for sure it was not on the semi-canonical 11x17 black on yellow strike poster.]

What were they doing on May 3?

Around the country, school administrators, government officials and cops were also feverishly sharing information and trying to plan their response to something they had never expected--a deeply militant and locally-centered national student strike.

Newspaper editorials ran the whole gamut, from full throated denunciations to timid declarations that we were right to be concerned and it was too bad that we were going about things in the wrong way.

On May 3, Governor Rhodes of Ohio, raging after the National Guard contingent he deployed to Kent State failed to stop the burning of the campus ROTC building the night before, said of student protesters in a table-pounding radio broadcast: They're worse than the brownshirts and the communist element and also the night riders and vigilantes. They're the worst type of people that we harbor in America. And I want to say this: They're not going to take over a campus.

Now we today we are used to hearing rhetoric on this order from yahoos like Glenn Beck and Rush Limbaugh directed at protesters, movie stars, Democratic elected officials and miscellaneous other targets whose sin is having a political outlook to the left of, say, Vlad the Impaler.

The difference is that these clowns are media figures, entertainers. Governor Rhodes held political power in the state of Ohio. He had a state police force and tens of thousands of National Guard troops to back up his big talk. So did California governor Ronald Reagan, who had had threatened campus demonstrators only a month earlier, on April 7, saying "If it takes a bloodbath, let's get it over with." So did President Nixon, whose Cambodia speech (which I quoted in the second of these May '70 posts) conjured up the threat of anarchy and warned that "Even here in the United States, great universities are being systematically destroyed."

Let me repeat, these people exercised state power, to use a fine old Marxist term. They ran the government. And while we knew that they were potentially capable of using the force at their disposal, we were also wrapped in a cocoon of privilege, white privilege for most of us and the class privilege that comes from being college students, being in a transitional class location en route, many of us, to professional and managerial careers.

Yes, white folks had been killed in protests--James Rector was gunned off a roof by Berkeley cops during the People's Park riot the year before. Yes, students at traditionally Black college campuses had been shot in cold blood by police--three had been killed just two years before at South Carolina State in Orangeburg.

So we knew they could kill us, but we didn't quite believe they would.

Click here to read this series from the beginning.

Click here to read the next installment.